Cultural Profile

The Nakoda, also known as the Yanktonai Sioux, split from the Sioux Nation during a civil upheaval in the 1600s. They moved northward out of the United States into Canada, creating a strong alliance with the Cree. By the early 1700s, they occupied the northern plains from the Red River to the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. As they roamed the rolling plains west of Lake Winnipeg, the Nakoda incorporated cultural aspects of the Plains Cree living to the north, and the Blackfoot to the south. In Alberta they became known as the Stony people, and elsewhere as the Assiniboine.

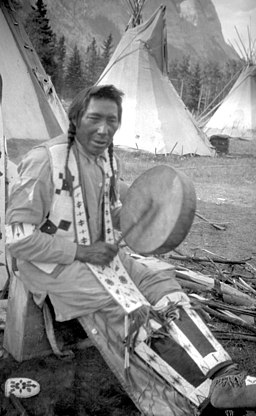

Bison featured prominently in Nakoda life and culture. No part of the animal was wasted; what was not eaten went into the making of most everything they owned. In nomadic groups of extended families, the Nakoda followed the migrating herds of buffalo and other resources across the plains, setting up camp at different locations. At each site they set up buffalo-hide teepees, some of which were as large as 30 feet in diameter.

Pemmican, a mixture of dried, shredded buffalo meat, mixed with fat and berries, was an invaluable dietary staple during their rigorous travels. Highly nutritious and easily transported, pemmican required no preparation and kept for long periods of time. In today’s context, pemmican–which was also a valuable trading commodity–could be described as the ‘powerbar of the plains.’ In camp, the women would simmer meat and vegetables in birch-bark or hide baskets of water that was ingeniously heated with scalding stones. The Ojibwe/Chippewa nameAssiniboine, bestowed on the Nakoda, means “one who cooks with heated stones.”

With the decimation of the buffalo population by 1880, the Nakoda experienced terrible hardships. Lacking access to their traditional food source, many on the reservations died of starvation. For the people of the five Nakoda/Assiniboine reserves in Saskatchewan and Alberta, the loss of the buffalo brought about irrevocable changes to their traditional way of life, yet it has never been completely lost.

Sponsor: Mr and Mrs Norman Rietze | Photos courtesy Wikimedia Commons and Flickr